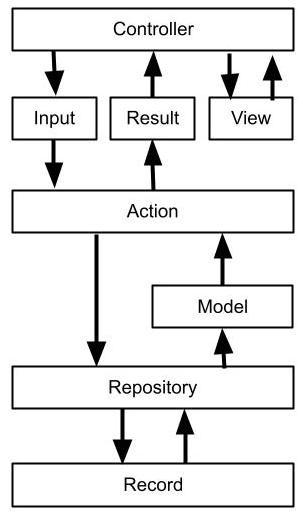

So far we have introduced new casts of objects that distribute the roles traditionally played by Active Record, decoupling the app’s business logic from Records and encapsulating them to database persistence. However, controllers are still sharing part of the responsibilities of business logic. In the Blog example, Articles Controller still sends the validate message to the input, which is a core logic that belongs to the business layer.

It is also important to note that in real world scenarios many other operations are involved in processing a request other than just input validation and a single call to the database. Emails are sent, jobs are enqueued, and requests to external services are performed, among others. If all this is handled at the controller level, the same smells previously explored will still be present, regardless of use of Repositories, Inputs, and Models. For those we need a boundary layer on top of the app’s business logic, so controllers can sit loosely on top of it and remain solely responsible for HTTP concerns. Enter Action objects.

Actions represent the entry points to the app’s core logic. These objects coordinate workflows in order to get operations and activities done. Ultimately, Actions are the public interface of the app’s business layers.

Rails controllers talk to the app’s internals by sending messages to specific Actions, optionally with the required inputs. Actions have a one-to-one relationship with incoming requests: they are paired symmetrically with end-user intents and demands. This is quite a special requirement from this layer: any given HTTP request handled by the app should be handled by a single Action.

The fact that each Action represents a meaningful and complete request-response cycle forces modularization for the app’s business logic, exposing immediately complex relationships between objects at the same time that frees up the app from scenarios such as interdependent requests. In other words, Actions do not have knowledge or coupling between other Actions whatsoever.

Actions respond to a single public method perform. Each Action defines its own set of required arguments for perform, as well what can be expected as the result of that method. The returned value is not any object, however. We have a special type of object dedicated to represent the outcome of an Action: Results.

Results are special Structs that are generated dynamically to accommodate a set of members. These members are inferred based on instance variables explicitly exposed by each Action. Since different Actions might want to expose zero to multiple values, they are always returned as members of a Result instance.

Regardless of the variables the Action might want to expose, a Result has one default member called errors, which holds any errors that might occur when the Action is performed. If Result errors are empty, the Result is a success; if there are errors present, however, the Result is a failure. This empowers Actions with a predictable public interface, so callers can expect how to evaluate if an operation was successful or not by simply checking the success or failure of a Result.

For the sample Blog app, let’s refactor the existing code to use Actions and

Results. The Result itself is a Struct with at least one member for errors:

class Result < Struct

class << self

def new(*members)

members << :errors unless members.include?(:errors)

super(*members)

end

end

def initialize(**values)

errors = values.fetch(:errors, [])

super(**values.merge(errors: errors))

end

def success?

errors.none?

end

endActions are specializations of the base Action class, which defines a few helper methods to generate Results. Each concrete Action is expected to define its own perform method thereafter and always return a Result. As mentioned above, the Action whitelists certain instance variables that are exposed in the Result that its perform method returns. In case of errors, the failure method can be called, which exits the perform method right away and returns a Result populated with the given errors.

class Action

module Decorator

def perform(...)

catch(:failure) do

super

result

end

end

end

class << self

attr_writer :exposures

def exposures

@exposures ||= []

end

def expose(*names)

@exposures += names

end

private

def inherited(subclass)

super

subclass.exposures = exposures.dup

subclass.prepend(Decorator)

end

end

def failure(*errors)

throw(:failure, result(errors: errors))

end

private

def result(members = {})

result_class = Result.new(*self.class.exposures)

values = self.class.exposures.to_h do |name|

[name, instance_variable_get("@#{name}")]

end

result_class.new(**values.merge(members))

end

endWe are now ready to write concrete Actions that return Results. Starting with a simple Action that finds an Article for a given ID. This Action defines its own Result as having an article member that contains the desired Article instance. Note that this Action always returns a successful Result.

class ShowArticleAction < Action

expose :article

def perform(id)

@article = ArticleRepository.new.find(id)

end

endHere’s an example of how an Action takes an Article Input and returns an Article Result. This Action checks if the input is valid, and proceeds with calling the Repository for persistence. If the input is invalid, however, it returns a failure Result populated with the validation errors.

class CreateArticleAction < Action

expose :article

def perform(input)

if input.valid?

@article = ArticleRepository.new.create(input)

else

failure(input.errors)

end

end

endExposed variables are optional. Some Actions can simply return an empty success Result as a return value, such as the Delete Article Action:

class DeleteArticleAction < Action

def perform(id)

ArticleRepository.new.delete(id)

end

endThese Actions (and others that handle updating and listing Articles) are used in the controller as follows:

class ArticlesController < ApplicationController

# GET /articles

def index

@result = ListArticlesAction.new.perform

end

# GET /articles/1

def show

@result = ShowArticleAction.new.perform(params[:id])

end

# GET /articles/new

def new

@input = ArticleInput.new

end

# GET /articles/1/edit

def edit

@result = EditArticleAction.new.perform(params[:id])

@input = ArticleInput.new(

title: @result.article.title, body: @result.article.body

)

end

# POST /articles

def create

@input = ArticleInput.new(article_params)

@result = CreateArticleAction.new.perform(@input)

if @result.success?

redirect_to(

article_path(@result.article.id),

notice: 'Article was successfully created.'

)

else

render(:new)

end

end

# PATCH/PUT /articles/1

def update

@input = ArticleInput.new(article_params)

@result = UpdateArticleAction.new.perform(params[:id], @input)

if @result.success?

redirect_to(

article_path(@result.article.id),

notice: 'Article was successfully updated.'

)

else

render(:edit)

end

end

# DELETE /articles/1

def destroy

DeleteArticleAction.new.perform(params[:id])

redirect_to articles_url, notice: 'Article was successfully destroyed.'

end

private

# Only allow a list of trusted parameters through.

def article_params

params.require(:article_input).permit(:title, :body)

end

endThe controller now has the single responsibility of abstracting away HTTP concerns, such as extracting data from request parameters and forwarding them to the proper Actions. According to the Result returned, the controller then crafts the appropriate HTTP response. Controllers don’t hold any logic regarding validations, persistence, or anything else behind an Action.

The combination of these additional layers of Actions, Results, Inputs, Models, and Repositories allows apps to have small objects with specific roles handling the business logic. The default Rails objects are specialized in single responsibilities, and the resulting architecture is one which requests are handled by a network of objects collaborating between themselves. These objects are easy to understand, test, and most importantly, much easier to change.