I still remember the joy I experienced after building my first Rails app. It was 2009, when I used Rails 2 to create a discussion board website. Everything was simple, quick, and easy to understand. After unpleasant experiences with Java and PHP for anything-web-related up to that point, I felt an incredible sense of liberation, like I could achieve anything I wanted with just a few commands and lines of Ruby. Needless to say, my first Rails app was a side-project maintained by a single person with very little functionality. Under those circumstances, everything was just perfect.

Soon after, I was doing Ruby on Rails as my full time job. At that time, I started engaging with different teams of developers, designers, and product managers to build fast-growing projects. Things still looked pretty good: green field projects where we got an advantageous headstart with a couple of Rails scaffolding and smart CRUD operations. As soon as an app would grow to a significant size, however, something interesting started to happen: the teams experienced an increasing drop in development speed, and the project backlogs would get filled with “technical issues” and “refactoring” tickets. People felt that the code needed to be rearranged in order to fix bugs and implement new features.

After moving to Canada in 2014 I got an engineering position at Shopify. Shopify was already famous for its huge Rails monolith that delivered incredible performance at an unimaginable scale. Over my years at the company I had the chance to work not only on Shopify’s core monolith but also create and contribute to multiple other Rails apps. At Shopify, I noticed that the phenomenon of growing Rails apps getting harder and harder to deal with was not exclusive to my previous workplaces. My focus then turned towards how to better organize these codebases so they could be easy to change regardless of the growing number of developers as well as lines of code required to keep them competitive and innovative.

Each Rails app I worked on had unique challenges, often related to its very nature, scale, and purpose. But with experience I started to notice that some challenges were quite common to all of them, especially in regards to code organization. For some reason, controllers and models always ended up overly large, business logic was hard to understand (and therefore hard to change), CI times slowed everybody down, and test suites were impossible to be executed locally in their entirety.

In these recurring situations, I really missed that joy I felt when I did my

first Rails app. “What did go wrong?” was in the back of my mind always. I

wanted to be able to experience the developer happiness I had from the very

beginning of my bundle exec rails new, all the way to the point the app is up,

running, and winning. As a developer lead, it became clear to me that, in order

to remain successful at building great products, a team must find solutions to

keep their codebases easy to change despite its size and complexity.

I knew that neither the problem nor the answers could lie within Rails itself. After all, I loved Rails for the things I used it for: great routing, convention over configuration, simple and easy to use APIs for the web, mailers, and jobs, a great persistence layer with Active Record, and more. It was my own responsibility to design my application logic responsibly, using the object-oriented powers of Ruby.

For that purpose, I started cataloguing the code smells I found recurrently in apps I worked on, and by borrowing ideas from different frameworks, teams, mentors, or by simple stubborn trial and error, I adapted patterns that helped me and my teams be more productive in our Rails apps. These patterns were not new; many of them in fact were decades-old and widely used in the enterprise world that I left behind once I started doing Ruby on Rails. Life is full of irony after all. After using and reusing these patterns, in part or in full, in multiple apps and teams, I had the chance to refine them to a point that some of them became very good defaults for my subsequent Rails apps.

People eventually took notice of this design, and started asking me if I had documented it somewhere. Reluctantly, I had to admit that I did not write about them anywhere at all. Everything was either in my head or in the Ruby code I had written in my past apps. Not only that made it difficult to share those ideas, but also meant that I had to reinvent the wheel whenever I created a new Rails app. I literally had to do some code archeology to remember the smells, patterns, and APIs, so I could implement them all over again.

And that is what motivated me to start this guide. This project intends to compile the most basic patterns I had used with my teams to build a sustainable architecture in Rails. Now I have the chance to give them names, to think about proper, reusable APIs, as well as to write proper documentation so future me and anyone else can understand the reasonings behind them.

This project also has given me the opportunity to write some reusable code as a Ruby gem, to make it easier to adopt these practices in new Rails apps. This is something I haven’t done previously; in my apps, I wrote and rewrote all these patterns from scratch. That being said, this guide focuses on the patterns themselves; anyone can adopt them in full or in part without having to install anything. In the end, these practices are just classic object-oriented design, and not an intricate new framework.

It is important to note that this work is, first and foremost, an experiment. As I mentioned before, I had used the patterns shipped in this guide in different scales and shapes, and they had helped me create a better maintainable code; this project as a formalized and integrated architecture, however, is at its very infancy. There are many questions without answers, and edge cases to be dealt with. The eason I am sharing this work early on is because I value transparency and I believe in the power of collaboration. I hope the contents of this experiment will spark constructive discussions that can create a virtuous feedback loop that everybody can benefit from.

Is this guide for me?

This guide is best suited for experienced Rails developers. If you are just getting started with Rails, I recommend starting with the official Rails Guides instead and not diverging too much from the standard Rails way until you are comfortable with those tools.

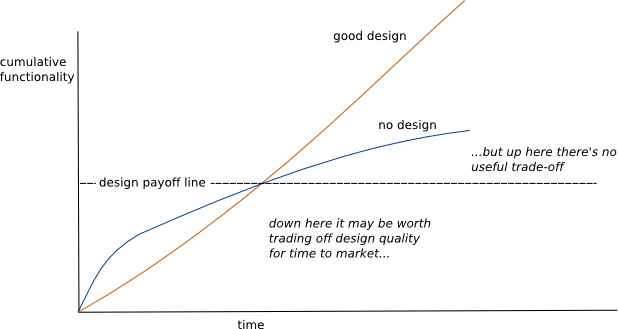

Like anything else in the universe, applying this guide involves a trade-off. It increases indirection in order to give your app a more robust foundation for further growth. This added indirection can only pay off once your app reaches a certain level of complexity. Smaller apps might be actually harder to deal with if this extra design work is not justified. This is made clear in the Design Stamina Hypothesis:

The question that remains is at what point in time the design activities should start; in other words, how can we identify that “design payoff line” when introducing an architecture such as the one proposed in this guide is justified. This is a tricky question, but in my experience, teams err much more often on the side of waiting too long than designing too early. A great way to develop a good foresight is to be in close contact with the businesses goals of the organization you work on. By knowing where the company is heading and what the growth plans are, you can make a more assertive decision if going with extra layers and indirection makes sense to your reality or not.

It is important to warn you that this guide is born from the opinion that having smaller objects with single responsibilities that collaborate with each other is better than having large objects that do many things. The goal of this project is not to teach object-oriented design, however. If you are new to this approach, it might be a good idea to start with some educational content in software design. If you are experienced with object-oriented design but disagree with this stance, then this guide might not make much sense to you.

Finally, this guide might only make sense for those who felt the pain. If, like me, you’ve been at that place of questioning your own design choices when building your app, or you feel trapped in procedural code that is hard to change. You might benefit from this architecture, or might be inspired by it to create your own solutions.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the teachings and inspiration from other works. Firstly, Sandi Metz’s Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby, as well as her talks, were invaluable for me being able to better rationalize around writing code that is easy to change. The concepts and ideas described in this guide also got a lot of inspiration from great projects such as Hanami, Trailblazer, and dry.rb. I highly recommend checking these projects out.

Many thanks to my teammates across companies that experimented with these patterns with me through the years. Their feedback in meetings, calls, and pull requests were indispensable for the maturity of these ideas. I am grateful also to the dozens of developers who read, shared, and commented on this content with constructive criticism. Your input helped immensely to filter the nonsense out and polish the good stuff.