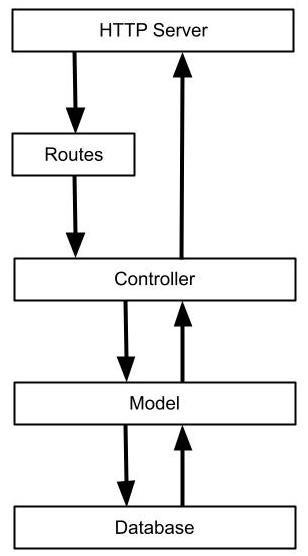

A standard Rails app responds to incoming requests by exchanging messages through a stack of framework layers. From the Routes level, a request is delegated to a Controller action that processes the request and returns an HTTP response. By default the stack can be simplified as the diagram below.

Auxiliary frameworks such as Active Job, Action Mailer, and Views can be called by controller actions as needed.

This stack alone is a perfect fit for most features, as long as their business logic is simple and lightweight. In the reality of production apps with a big surface area, this is hardly the case. Processing requests and crafting responses involves many steps, with preconditions to be checked, conditional statements, validations, and multiple combinations of different responses.

Since the stack above does not bring answers to how the business logic should be structured, apps are left with the homework of properly organizing the orchestration of steps required to process use cases. Software design is a costly exercise, however, and very often overlooked or ignored; so business logic is simply left to creep around the same initial Rails stack in a procedural fashion. This lack of design can be spotted by identifying some common signs of problems with software design, also known as code smells.

A code smell is not necessarily an issue or bug: it is simply a surface indication that there could be an underlying problem with how the code is designed. As pointed out by Martin Fowler, "smells aren't inherently bad on their own - they are often an indicator of a problem rather than the problem themselves."

The lack of proper design for organizing business logic produces some very common smells in Rails apps. The list below compiles a few recurrent ones.

Illegible Routes

Routes map request patterns to controller actions. It employs a specific DSL that is optimized for resourceful routes: mappings that follow the seven standard REST operations for a given controller.

In growing production apps, the overload of features and changes takes a toll in the routes organization, leading to an increasing number of non-resourceful routes to creep in, constraints to create exceptional mappings for edge cases, repetition, and so much more. The result is a routes file that is impossible to be deciphered.

Convoluted Controller Callbacks (Before Actions)

Before Actions, the popular callbacks for controller actions, are handy tools for checking and early responding to some common preconditions such as throttling and authentication.

After multiple iterations, bug fixes, and features added on top of one another, Before Actions are abused in order to handle a myriad of convoluted preconditions. It is not uncommon to see controller actions that, in order to be executed, need to pass many Before Actions.

These callbacks might also be conditional, or apply to just a subset of actions in a given controller, which further impedes understanding of what is actually happening in a controller. Not to mention when controllers inherit Before Actions from their ancestors.

Large Actions

The ultimate smell in Rails apps.

Incoming requests are handled by actions, the controller public methods. These methods are called once for each request, and they are responsible for crafting an appropriate HTTP response.

In theory, actions would collaborate with other layers of the application so they remain lightweight. The reality of most apps is very different: actions are long sequences of procedural code, with nested conditionals and coupling with multiple constants.

The reason why actions are long and complex in many apps is because they are just the most convenient place in the entire Rails stack to shelve quick changes and fixes. Given that controller methods are the predictable paths of the code to be executed for a request, developers often can ignore all the rest and inject the code they want straight in the controller action and the job is done.

Obviously this is not a good design nor a healthy practice long term. As actions accumulate complex and long procedural code they become very difficult to understand, its behaviour unpredictable, leading to bugs and an increasingly slower development process. Large actions also negatively affect testing: since controller’s behaviours are asserted with integration tests, in order to assure coverage a lot of integration test cases are written as system and browser tests that are much slower than unit tests, ultimately leading to terribly slow CI times.

Private Methods in Controllers

This specific smell is a consequence of long actions. A common refactor employed to address long methods such as actions is to break the code down into smaller private methods. This refactor is a worrisome anti-pattern that replaces the long method smell with a much worse-smelling collection of needless indirection.

It is interesting to find Rails apps in which controllers have a relatively lightweight collection of actions that actually hides a long and complex private interface. Masking out complex actions by using private methods doesn’t do any good, and actually increases the overall size of controller classes.

A no-brainer fix for the private methods smell is to replace their calls in the action code with their contents. At least long actions are honest about their faults, exposing to the world their dire complexity.

Single-Use Mixins

Another attempt to hide the complexity of large actions is to break them down in smaller single-use methods, but instead of marking them as private in the controller, they are moved to a module that is included in the inheritance chain. Sometimes referred to as Concerns, these mixins are simply adding needless indirection without addressing the fact that the controller is doing too much.

Similarly to private methods, these mixins should be removed and their code incorporated back into the controller that includes them. Not as separate private methods, but to have their body reinserted directly in the actions that call them.

Extensive Ruby Code in Views

Views are templates where data is interpolated to generate the response body, usually ERB files that output HTML. Because these files can accommodate any Ruby code, they are often abused with nested conditionals, variable assignments, and even direct database queries. This is due to the overflow of business logic beyond controller actions and models: developers know their actions and models are already too big, so extra code simply finds the path of least resistance in view files. The problem extensive Ruby code in views cause is cluttering: files that were supposed to be made of mostly markup and data interpolation become long sequences of conditionals and procedure code.

Coupling in View Helpers

When additional presentation logic is required in view files helpers can be of use. View helpers are functional mixins that processes the given arguments and returns bits of output that are later interpolated in view templates. As of any other layer in the Rails stack, however, they are also abused to accommodate intrusive business logic beyond their initial responsibilities.

The most obvious symptom of unhealthy view helpers is when they are coupled to other parts of the codebase, referencing constants from models, controllers, and more. This is commonly seen when view helpers depend on instance variables from controllers; ideally helpers should receive all the data they require via arguments. This ensures that they are kept lightweight, idempotent, and easy to test.

Another recurring consequence of this coupling is that it makes testing view helpers quite painful. Often developers simply give up in giving helpers proper test coverage due to how difficult it is to assert their behaviour.

Active Record Callbacks

Rails offers hooks to execute certain routines before, after, and around Active Record operations. For example, checks and transformations before a record is saved in the database, or emails and jobs can be performed after a successful update.

Since these callback methods are called implicitly by the framework, they can become inadvertently cumbersome. By simply reading the Active Record model's code it is very hard to reason about everything that is happening around method calls and callbacks. Similar to controller callbacks, these can also apply to subsets of methods or be conditional to certain states, which further hinders understanding the possible logic paths and makes code very hard to change and maintain.

The very existence of callbacks in Active Record models is a smell in itself: there is no reason not to replace them with explicit, direct method calls through more thoughtful and meaningful software design.

Lazy Loaded Active Record Associations

Active Record is a robust and complex framework that abstracts in Ruby all the interface with the relational database. A significant subset of the framework is dedicated to abstract operations around foreign keys and references between database tables, the Active Record Associations.

Using macros such as has_many and belongs_to, associations allow Active

Record models to define how they are linked to one another, dynamically defining

methods that return collections of associated records for a given Active Record

model instance. This is a classic behaviour in Rails apps that allow writing

features around nested resources very easily.

The problem with Active Record Associations is that these methods implement lazy loading by default. The business logic might simply send a message to read data from an already loaded method and inadvertently end up performing database queries from the view layer. This is ultimately the source of performance issues such as N+1 queries.

Giving Active Record models extra methods that reference and return instances of other model classes is also a precedent in which much of customizations are built upon, which makes it very hard to change code afterwards and fix slow queries. Knowledge regarding assocations between models should, therefore, be limited to optimization of database operations, such as in joins.

Fat Active Record Models

When looking for a suitable location to inject business logic, many developers prefer to place this in Active Record classes. This is usually justified as a more object-oriented approach, since controllers easily become too procedural as seen in the previously listed smells.

Over time, Active Record models get overloaded with all sorts of responsibilities, from validations that are unrelated to any of their attributes, to sending emails, making network calls, and enqueueing jobs. These are written as a multitude of class and instance methods, usually quite long ones.

This excessive amount of methods and behaviour in Active Record models reach its worst point in specific classes known as the god objects of the app: resources that are so overloaded with behaviour that they have references to all other main constants of the codebase, as well as being referenced by everybody else.

Active Record classes that are crowded with methods bear too many responsibilities and are very hard to change. And the harder they are to change, the less they are to be eligible for refactorings. These objects become then the oldest and hardest technical debts to be paid.

Private Methods in Active Record Models

Similar to the problem of private methods in controllers, the creation of a private interface in Active Record models is an antipattern to hide away the fact that those classes are just too big and do too much. Like in controllers, there should not be private methods in models except for reusability or if referenced in macros when required by the framework.